Dieter Rams and ten principles for good design

Dieter Rams is one of the most influential designers of our time. The iconic products he designed during his forty-year career at Braun and Vitsœ are in homes and museum collections around the world.

Dieter Rams was born in Wiesbaden, Germany, in 1932. His early exposure to craft came through his grandfather, a carpenter, whose workshop introduced him to materials, precision, and the value of making things well. This grounding in craft shaped Rams’s outlook long before he entered industrial design.

After receiving early recognition for his carpentry work, he trained as an architect during the post‑war reconstruction of Germany in the early 1950s, a period defined by scarcity, rebuilding, and a need for functional clarity.

In 1955, encouraged by a perceptive friend, Rams applied for a position at Braun, the German manufacturer of electrical products. He was hired by Erwin and Artur Braun, who were reshaping the company following their father’s death. Rams’s initial role focused on modernizing Braun’s interiors, but his proximity to engineers and product developers quickly drew him into product design itself.

Rams became closely associated with the intellectual environment of the Ulm School of Design, the successor to the Bauhaus. He worked alongside figures such as Hans Gugelot, Fritz Eichler, and Otl Aicher, whose emphasis on systems, clarity, and social responsibility strongly influenced his thinking. This context helped Rams move beyond surface aesthetics toward a rigorous relationship between form, function, and use.

One early and widely cited example of this approach was the SK4 radiogram (1956), for which Rams introduced a clear Perspex lid. The decision was not decorative; it made the product visually lighter, more honest about its construction, and easier to understand. By 1961, Rams was appointed head of design at Braun, a position he held until 1995. During this period, Braun’s products became internationally recognized for their restraint, coherence, and usability.

At Braun, Rams established a systematic design language rooted in function and reduction. Products were stripped of unnecessary elements and organized with careful logic. Controls were placed where they were needed, forms were simplified, and materials were chosen for durability rather than novelty. As Rams later explained, the clarity of Braun’s products emerged from the deliberate ordering of elements and the search for a coherent whole.

Design decisions were never arbitrary; each detail served a purpose.

This approach reshaped how electronic products were perceived. Rams treated objects not as statements, but as tools meant to fit quietly into everyday life. His modular systems, clean lines, and neutral forms allowed people to focus on use rather than appearance. The goal was not to impress, but to support daily routines with reliability and calm. In doing so, Rams set a standard that influenced generations of designers across consumer electronics, furniture, and digital products.

By the late 1970s, Rams became increasingly concerned about the growing visual and environmental clutter of the manufactured world, which he described as an “impenetrable confusion of forms, colors, and noises.” Recognizing his own role in shaping that environment, he posed a fundamental question: is my design good design?

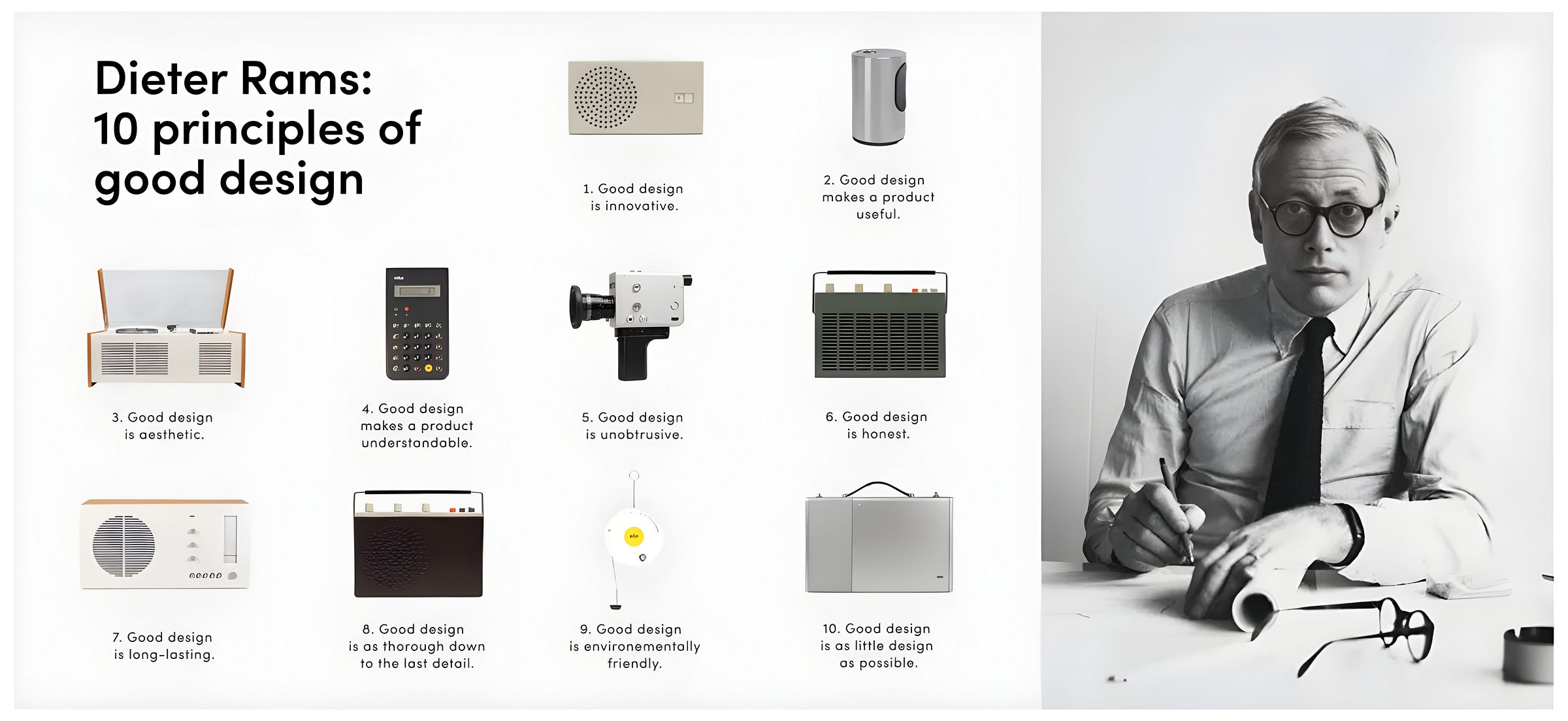

From this reflection emerged his formulation of principles intended not as rules, but as criteria for judgment, and expressed in his ten principles for good design.

Dieter Rams’ ten principles of good design

1. Good design is innovative

The possibilities for innovation are not, by any means, exhausted. Technological development is always offering new opportunities for innovative design. But innovative design always develops in tandem with innovative technology, and can never be an end in itself.

2. Good design makes a product useful

A product is bought to be used. It has to satisfy certain criteria, not only functional, but also psychological and aesthetic. Good design emphasizes the usefulness of a product whilst disregarding anything that could possibly detract from it.

3. Good design is aesthetic

The aesthetic quality of a product is integral to its usefulness because products we use every day affect our person and our well-being. But only well-executed objects can be beautiful.

4. Good design makes a product understandable

It clarifies the products structure. Better still, it can make the product talk. At best, it is self-explanatory.

5. Good design is unobtrusive

Products fulfilling a purpose are like tools. They are neither decorative objects nor works of art. Their design should therefore be both neutral and restrained, to leave room for the users self-expression.

6. Good design is honest

It does not make a product more innovative, powerful or valuable than it really is. It does not attempt to manipulate the consumer with promises that cannot be kept.

7. Good design is long-lasting

It avoids being fashionable and therefore never appears antiquated. Unlike fashionable design, it lasts many years - even in today’s throwaway society.

8. Good design is thorough down to the last detail

Nothing must be arbitrary or left to chance. Care and accuracy in the design process show respect towards the consumer.

9. Good design is environmentally friendly

Design makes an important contribution to the preservation of the environment. It conserves resources and minimizes physical and visual pollution throughout the lifecycle of the product.

10. Good design is as little design as possible

Less, but better - because it concentrates on the essential aspects, and the products are not burdened with non-essentials. Back to purity, back to simplicity.

Implications for designers today

Rams’s principles still remain relevant because they address judgment rather than style. They encourage designers to evaluate decisions through usefulness, clarity, and restraint. Taken together, they form a practical lens for reviewing work: what can be removed, what can be clarified, and what truly serves the user.

For designers, Rams’s work also demonstrates the value of consistency over time. His influence did not come from isolated objects, but from decades of coherent decisions made within constraints. This long view, designing systems rather than statements, offers a durable model for contemporary practice.

Recognition and legacy

Rams’s contributions have been widely recognized. He was named Royal Designer for Industry by the Royal Society of Arts in London and received honors from international design institutions, including the Society of Industrial Artists and Designers and the Industrial Designers Society of America.

In 1995, he published the book “Less but Better” reporting his design philosophy and his main products produced at Braun.

Dieter Rams’s legacy lies not only in the products he designed, but in the standard he set for responsibility, clarity, and restraint. His work demonstrates how design can serve people by reducing noise, resisting excess, and focusing on what is essential. For designers seeking lasting impact, his career offers a clear lesson: design matters most when it quietly improves everyday life.

Rams today

Dieter Rams is now in his early nineties and living in Germany. He continues to be involved through interviews, archival projects, and exhibitions that revisit his work and its relevance for contemporary design.

He still improves his designs to this day and is often cited by a new generation as a key influence on their work that is shaping the 21st century.

Resources

Profile — Design Museum Collection

Profile — Braun designers

Works— The JF Chen Collection

Book — Less but Better

Documentary — Rams, dir: Gary Hustwit

Color Palettes — Figma file

Poster — Ten principles, printable

Wallpapers — Blog, Arun Venkatesan

Designer Portraits

This article is part of Designer Portraits, a series within Design, Explained.

We look at influential designers, not to celebrate style, but to understand judgment. How they thought. How they decided. Why their work still holds up when trends fade.

More portraits are coming.

If you want to be notified when new Designer Portraits are published, subscribe to Design, Explained. No noise. Just clear thinking, delivered when there is something worth reading.